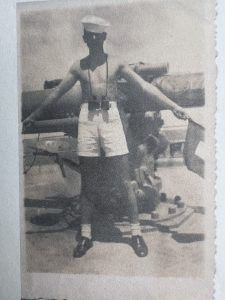

Navy Signalman Hartzell Sherrill

Eighty years ago today, a 22-year-old farm boy from Pledger, Texas, helped make history.

The D-Day Invasion that launched on June 6, 1944, had been the subject of top-secret planning for months. But Navy Signalman Hartzell Sherrill – my dad – and the crew alongside him on the SS Charles M. Hall were clueless as to what they were about to experience. It was an invasion so audacious, and so historic, they likely never could have imagined it.

My dad’s story is just one of the stories of the 160,000 allied troops – 73,000 Americans – who witnessed D-Day. With most of the survivors now well into their 90s or beyond, only a few may still be alive to tell their stories. Only 119,550 total WW2 veterans were still living in 2023, according to the National WW2 Museum in New Orleans.

As each generation moves one notch farther removed from a personal connection to D-Day, telling these stories becomes ever more important. Today, on the 80th anniversary of one of the most important battles every fought to protect our way of life, I’m sharing the story of just one young hero from Matagorda County, Texas.

“On December 27, 1941, just 20 days after the Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor, approximately 200 young men assembled on the second floor of the US Post Office Box on San Jacinto Street in downtown Houston. I was among that group,” wrote Hartzell Sherrill in his memoir. “A military officer asked us to hold up our right hand and repeat after him the pledge required to enter the US Navy. I had requested a radio operator’s school, and soon six of us, all 18 to 19 years old, assembled at the Southern Pacific Train Station off Washington Avenue in Houston, for departure to communication school in Los Angeles.”

Binoculars and flags were important parts of a signalman’s equipment

Assignment: Navy Signalman

His timing aligned with a new Navy initiative to place an Armed Guard Unit aboard the country’s 1,375 merchant ships, whose critical job was to deliver troops and supplies needed for the war. Each merchant ship carried a compliment of approximately 45 men, plus the Armed Guard Unit comprising 15-25 Navy gun crew and one Signalman. The unit worked closely with the ship’s captain and senior officers to maintain a state of readiness at all times for any emergency. By the end of the war, nearly 145,000 men served in these units, on 6,236 American and allied ships.”

The Signalman’s job combined visual communications and advanced lookout skills. They were to transmit, receive, encode, decode and distribute messages between ships and ship-to-shore. To avoid enemy interception, they used visual transmission systems including flag semaphore, visual Morse code, and flaghoist signalling.

At Omaha Beach, for example, Navy Signalmen set up a beach communications station between ships and shore using a semaphore light (able to be seen from afar) and Morse code to pass messages from land commanders to ships offshore. The signalman with the telescope read the ships’ semaphore signals and passed them on, according to archives from the Naval History and Heritage Command.

“Though seemingly cumbersome and quaint, visual signaling offers an advantage over radio communications through its security,” noted The USS Midway Museum’s blog. “Since radio waves can travel great distances, they can be intercepted, and perhaps understood, by opponents. Furthermore, a radio signal, even if indecipherable, can be traced to reveal the location of the sender. Visual signals, however, require a line-of-sight connection between sender and receiver, often at distances that render the consequences of enemy interception moot. Therefore, they are useful in communicating within a formation of ships within visual range of one another, without running the risk of detection from without.”

A replica of the EC2 Liberty Ship similar to the ones my dad served on, on display at the National WW2 Museum in New Orleans

An Uncertain Destination

Within five months after enlisting, on May 25, 1942, Seaman 1st Class Hartzell L. Sherrill boarded his first ship in New York. There, as the Signalman, he spent most of his time on the bridge in close proximity to the captain and ship’s officers, so that the visual messages sent and received could be quickly conveyed. Over the coming two years, his ranking would grow and his assignments would change to other ships – the SS Alcoa Polaris, and ultimately to the SS Charles M. Hall in March 1944. That assignment would prove historic.

“We learned that the SS Charles M. Hall would be part of a convoy of 100 ships leaving New York. German submarines were very active on the route that we would be taking and expected losses would be 10% – 10 ships,” he wrote. “We were in a state of radio silence and messages would be by flag hoists or flashing light using Morse code. I spent most of every day on the bridge and was on call 24 hours daily.

We left the harbor and entered the open sea to begin convoy formation. The Statue of Liberty could be seen as we departed, an impressive sight. It would have even more meaning to us when we returned following this mission. It seemed to take a lifetime getting all the ships in their proper place in the convoy. There were several columns with each column having about 10 ships. I was thankful that we were not on one of the outside columns, as I hoped that would give us a little buffer if a submarine attack occurred. We were definitely not alone; there were several destroyer escorts operating on all sides, and we also had one Baby Flat Top Aircraft Carrier.”

The convoy was forced to execute evasive maneuvers multiple times to avoid submarine activity as it crossed the cold and rough waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. Upon arrival finally at Glasgow, Scotland, the crew began unloading war material almost immediately. Alterations were then made to the ship to accommodate troops and their equipment – guns, trucks, tanks, jeeps.

These were among the flags used by signalmen during the D-Day invasion, on display at the National WW2 Museum in New Orleans

A Deadline That Had to be Met

“It seemed as though there was a deadline that had to be met. We knew that something big was about to take place in the near future but we didn’t know where or when. The Armed Guard crew was told that we needed to be prepared for the possibility of the use of mustard gas by the Germans and we were sent ashore several times to learn how to use a gas mask.

By the first of May, we moved to an anchorage somewhere north of Glasgow, where many ships were already. And then in late May, we moved to Newport, Southern Wales, where we began taking on troops and their equipment in preparation for what we later learned would be the Normandy Invasion. Little did we know that there were hundreds of ships taking on troops and their equipment just as we were. By now we were into the first week of June, and heavy seas postponed the original day of the invasion. We waited for the next day to bring better weather, standing watch in four hours on and four hours off.

Orders were given early the next day – June 6, 1944 – to move out. The invasion was reality. The burning question was what can we expect. We soon found out.”

Visitors marvel at the massive build-up of ships and aircraft in the Normandy Invasion, as depicted in this display at the National WW2 Museum in New Orleans

The Mightiest of Endeavors

At daybreak that morning, the largest armada every assembled stood off the Normandy coast of France – nearly 5,000 ships of all types. President Franklin D. Roosevelt called it “a mighty endeavor to preserve our civilization and to set free a suffering humanity.”

“The number of landing craft and ships in the sea and the number of planes in the air almost defied imagination. We were at the Omaha Beach area. Our group formed two columns. We were the second ship in the column on the right. The second ship on our left hit a mine and was badly damaged. We anchored just out of the range of the guns on the cliff. A cargo net was dropped over the side of our ship and soldiers began climbing down to waiting landing craft for a short trip to the beach head.

Mine sweepers were busy clearing mines from the sea bed. The Battleship Texas was firing its big guns as it cruised along parallel to the shore. Landing craft of all types were everywhere; they took men to the beach. There seemed to be so many planes in the air that surely there wasn’t enough room for just one more plane. Waves of bombers headed inland, dropped their load and as they were returning, another group took up where they left off. In a matter of hours, old ships that had been destined for the scrap pile were towed to a place parallel with the beach and sunk to form a breakwater. We could see landing craft operating between the shore line and the breakwater, and others beached to discharge men and equipment.”

His ship made a total of 15 trips from Southampton, England, to the Omaha Beach carrying troops and their supplies. “The night of the first trip to Omaha Beach kept us all on the edge. Daylight was very long and the nights very short. German air raids always came at night. It was dark, and we could not see the planes as they passed over and dropped their bomb loads. The screaming sound of the falling bombs was such an eerie sound. We lucked out that night as the bombs fell harmlessly in the water between our ship and the one nearest to us.”

The fighting at Normandy persisted through July 1944, as the Allied forces pushed the Germans further inland. Round trip activity to the beach slowed down after several weeks. After the initial 15 round trips from Southampton, England, to Omaha Beach, the SS Charles M. Hall made two more trips to Utah Beach. “I don’t have any idea the number of troops and equipment that we delivered to those beaches but it was a lot,” he wrote. After a final trip up the Seine River to Rouen, France, orders were given to return to the states.

The route across the English Channel from Southampton, England, to Omaha Beach

One of the Lucky Ones

My dad’s Naval service was far from over, and he faced many more harrowing crossings and close calls. In serving his country, he saw the world – the best and the worst of it. He made friends, he lost friends.

A total of 4,414 Allied troops were killed on D-Day itself, including 2,501 Americans. More than 5,000 were wounded. Untold troops were MIA.

“Casualties were great. It wasn’t unusual to see bodies floating in the water. I am certain those men were classified as Missing in Action. A few times we would see a body floating in the open sea as we made the return trip to England. I would be instructed to send a message to our escorts. The escort would acknowledge the message but never change course, and so another Missing in Action.”

Daddy was one of the lucky ones, to return home. At Camp Wallace sometime before noon on December 11, 1945, he and other veterans were thanked for having served and handed a certificate showing Honorable Discharge. His Navy story was over.

There are so many stories of other ordinary people who did extraordinary things when the world needed them. He never spoke of his service until many, many years later – in fact, not until after taking an Honor Flight to Washington, DC, on which he and his fellow WW2 veterans were thanked and honored by total strangers at every turn.

These incredible individuals – the Greatest Generation – never saw themselves as heroes. But each of us owes each of them so much. On this 80th anniversary of D-Day, let’s all say a “thank you for your service.” We can only pray that should our world ever need us to step up as they did, we will have the courage to honor them with glory.

Daddy lived to the age of 97, and would have been 102 on this D-Day anniversary.

Blog / November 13, 2023

Magnificent Moab: Southeast Utah's Mecca for Outdoor Adventure